![]()

The Insurrection Act is an old statute with a modern purpose. It is a legal bridge between two truths that sit uneasily together. One truth is that the US is a union of states with real sovereignty in matters of policing and public order. The other truth is that the US is one nation with one set of federal laws, one Constitution, and one federal government charged with executing its laws everywhere. When those truths collide, a republic needs a rule for who must yield, and under what conditions. The Insurrection Act supplies that rule.

To see why, start with the early Republic. The Constitution authorizes Congress to call forth the militia to execute the laws of the Union, suppress insurrections, and repel invasions. It also makes the President Commander in Chief once those forces are in federal service. Congress implemented this constitutional design through the Militia Acts of 1792 and 1795. Those statutes gave the President the power to summon state militias to confront insurrections and invasions, but they did so with caution and with checks. One of those checks was the requirement, in some situations, of a judicial certification that ordinary law enforcement was overwhelmed. Even at the founding, Americans understood the tradeoff. A government that cannot enforce its laws will not stay a government for long. A government that casually deploys soldiers against its citizens risks becoming something else.

George Washington’s response to the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794 put that tradeoff into practice. The federal government acted. It did so through legal channels, and it did so to enforce federal law. The core idea was not punishment. It was the preservation of a basic fact about political order, that laws will be executed even when a region decides it would rather not.

By 1807, Thomas Jefferson faced problems that the militia framework did not fully cover. The Republic confronted frontier instability, cross border threats, and a particularly ominous episode, the Burr conspiracy, a suspected plot that combined private armed ambition with the prospect of rebellion in the west. Jefferson concluded that the government might need to respond quickly, and that relying only on state militias might be too slow, too uneven, or too dependent on local will. He therefore sought statutory authorization to use regular federal forces at home. Congress responded with the law signed March 3, 1807, an act authorizing the employment of the land and naval forces of the United States in cases of insurrections.

The 1807 Act is sometimes described as a power grab. It is better understood as a recognition of something the Constitution already implies. A federal government that must enforce federal law cannot be structurally dependent on state cooperation at the very moment that state or local actors are obstructing federal law. The 1807 Act supplemented the existing militia call up authority by allowing the President to employ the Army and Navy for the same purposes whenever it was lawful to call out the militia. It did not create new crimes. It did not declare martial law. It supplied a tool, and it placed that tool inside a legal frame.

Over the next 2 centuries the statute evolved in response to crises that tested the boundaries of federal authority. The most significant expansions came with the Civil War and Reconstruction. In 1861, as rebellion against US authority erupted, Congress broadened the scope of the law to allow the President to act not only to suppress insurrection but also to enforce the faithful execution of federal law when rebellion or unlawful obstruction made ordinary enforcement impracticable. That language survives today in what is now codified in 10 USC §§ 251 to 255. In 1871, during Reconstruction, Congress expanded the statute again to address violent conspiracies that deprived people of constitutional rights when state authorities could not or would not protect those rights. That expansion, associated with the Ku Klux Klan Act, recognized that lawlessness can be both private and political. It can be a mob, and it can be a regime of intimidation that substitutes local coercion for federal rights.

A few years later, Congress passed the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, generally prohibiting use of the Army for domestic law enforcement, with a crucial exception, where Congress has authorized it. The Insurrection Act is the central authorization. That is not a loophole. It is the structure. Congress barred routine military policing precisely because it preserved an emergency statute to be used when civilian authority fails or is obstructed.

It is worth recalling that Congress has revisited this balance even in the modern era. After Hurricane Katrina, Congress briefly expanded the Insurrection Act through a provision in the 2007 defense authorization act, signed in October 2006, to make it easier to deploy troops without a governor’s request in certain emergencies. The governors of all 50 states objected, and Congress repealed the expansion in 2008. That episode is revealing. It shows that Americans remain wary of turning a last resort authority into an everyday administrative convenience. It also shows that the core authority is not an accident or a relic. It is a deliberate part of the constitutional settlement.

The present statute is best understood by separating its three main pathways. First, at a state’s request, the President may use the militia and armed forces to suppress an insurrection in that state. Second, the President may act unilaterally when unlawful obstructions, combinations, or assemblages, or rebellion against US authority, make it impracticable to enforce federal law by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings. Third, the President may act unilaterally to suppress insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy that either deprives people of constitutional rights when state authorities cannot or will not protect them, or that opposes or obstructs the execution of federal law or impedes the course of justice under those laws. In the unilateral pathways, the statute also requires a proclamation to disperse, an old but sensible procedural step that signals the seriousness of the move while affording a last chance for compliance.

This structure is not merely theoretical. Presidents have used it across the nation’s history, in ways that illuminate both its necessity and its risks. Jefferson used it in 1808 to enforce the Embargo Act amid smuggling and resistance near Lake Champlain. Andrew Jackson invoked it in 1831 in response to Nat Turner’s slave rebellion. Abraham Lincoln relied on the statute and its antecedents at the outset of the Civil War to call forth the militia against secession. Ulysses S. Grant invoked it repeatedly during Reconstruction to crush the Ku Klux Klan and related insurgencies, including in South Carolina, Louisiana, and Mississippi, when paramilitary violence threatened republican government and the rights of black citizens.

The statute was also used in labor unrest, a category that many modern readers find uncomfortable. Rutherford B. Hayes invoked it in 1877 during the Great Railroad Strike. Grover Cleveland invoked it in 1894 during the Pullman Strike when federal mail delivery and interstate commerce were obstructed. Woodrow Wilson used it in 1914 during the Colorado Coalfield War. Warren G. Harding invoked it in 1921 during the Battle of Blair Mountain. Franklin D. Roosevelt invoked it in 1943 to quell the Detroit race riot. The civil rights era provides the most morally clarifying examples of federal supremacy in action. Dwight D. Eisenhower invoked it in 1957 to enforce desegregation at Little Rock, federalizing the Arkansas National Guard and deploying the 101st Airborne to ensure federal court orders were obeyed. John F. Kennedy invoked it in 1962 at the University of Mississippi after violent resistance to James Meredith’s enrollment, and again in 1963 in Alabama when Governor George Wallace attempted to block integration. Lyndon B. Johnson invoked it in 1965 to protect the Selma to Montgomery marchers, and in 1967 and 1968 to respond to severe riots. Ronald Reagan invoked it in 1987 to end a prison riot in Atlanta. George H. W. Bush invoked it in 1989 in the US Virgin Islands after Hurricane Hugo, and in 1992 during the Los Angeles riots, the last time it has been used to deploy federal troops on US soil.

This history yields a sober lesson. The Insurrection Act is neither inherently tyrannical nor inherently noble. It is a tool. Its morality depends on the predicate facts and on the aims and discipline of its use. When Eisenhower enforced federal desegregation orders against state obstruction, the statute served constitutional equality. When federal forces crushed violent riots that local authorities could not control, the statute served public safety. When the statute was used in labor disputes, critics argued that it served private power and suppressed workers. When Gen. Douglas MacArthur exceeded orders in 1932 against the Bonus Army, public outrage reflected the danger of confusing protest with rebellion. If the Insurrection Act is to be justified in any given case, the justification must be fact sensitive, goal specific, and limited by the Constitution.

That brings us to Minnesota. The question is not whether the Insurrection Act can be abused. It can. The question is whether current conditions in Minnesota, as described by federal officials and as evidenced by sustained violence and obstruction, fit within the statute’s predicates and within the broader constitutional duty of the President to take care that the laws be faithfully executed.

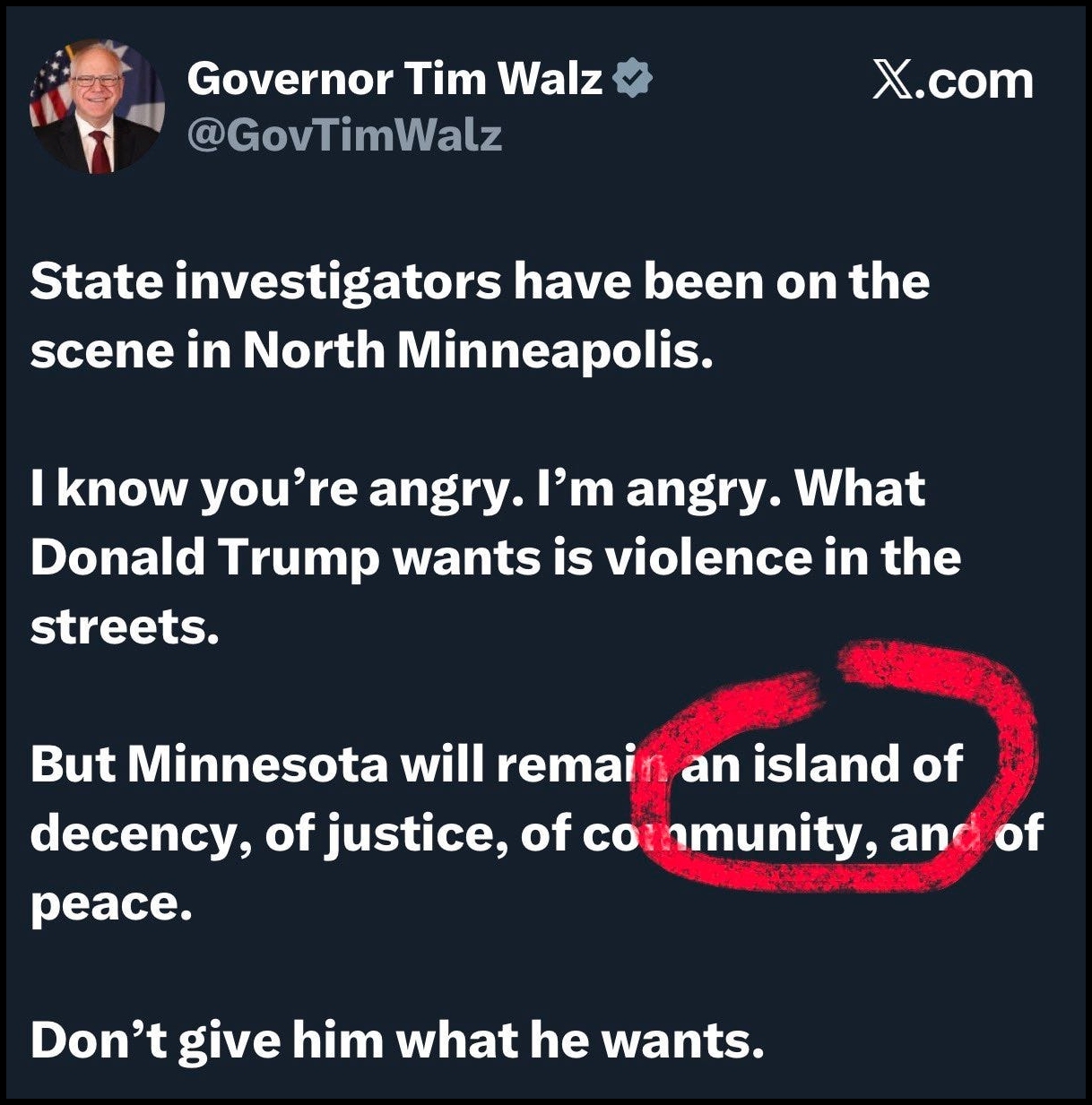

Here is the picture that matters. Federal immigration authorities are conducting a sustained enforcement operation in Minnesota, Operation Metro Surge. State and local leaders have reacted with open hostility. Minnesota’s Attorney General, together with Minneapolis and St. Paul, has sued to halt the federal surge, calling it an unprecedented invasion by armed agents. Governor Tim Walz has denounced the operation as organized brutality and placed the Minnesota National Guard on alert through a warning order threatening to deploy them to ‘protect’ residents from immigration officials. Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey has demanded that ICE agents leave the city, using profane language that signals a posture of outright defiance. This breakdown in cooperation has coincided with violence against federal personnel and disorder in the streets.

When Obama was president the media happily went on ride-alongs with ICE while they did this exact same thing!

The media and the liberals in state offices all loved ICE back then.

The original idea behind “sanctuary” cities/states was that illegals who were VICTIMS of criminals wouldn’t be afraid to be deported when they reported crimes against themselves.

It was originally meant to assist in getting illegal criminals and other criminals into custody.

When did all that change?

Cartels have a stranglehold on entire communities of illegals.

They even tried to do apartment building takeovers of non-illegals in Colorado.

But the governments of cities and states protecting cartels from federal law enforcement?

Mexico’s politicians showed that gov’t officials can be bought off.

I’m pretty sure the law-abiding illegals had been thrown under the bus by this unholy alliance between cartels and state/local officials.

I see where some low down Bottom Feeder/Sewer Dweller is introducing a Bill to Abolish ICE just another UN/CFR/Globalists and Traitor like all the rest of the Dem-O-Rats