![]()

This is one of those videos that works on a great many levels, humorous and otherwise, because this really is one of the most simultaneously important and slippery questions in humanity:

“Are we the baddies?” (And how would we know if we were?)

I suspect that the world would be a much better place if considerably more of us were asking this question of ourselves on the regular and being most fastidious about our answers, because we all do it sometimes. We all step too far, act like a jerk when we didn’t need to, respond uncharitably to ambiguity, and project our own views of others onto others out of laziness or frustration. These are matters of small degree, but they build into large structures of antipathy and incompatible semantic and worldviews, and I suspect that a great deal of the seemingly high-flashpoint hatred and vilification of the moment resides in this: we have stopped talking to one another and increasingly lack any basis or tools to start.

It’s become a subjective morass, and the path out tends, to my mind, to lie in objectivism. But to walk it, we must first agree about some objective facts, and so I’d like to add just one, a single question in service of a single foundational tenet from which we can, from first principles, build.

It’s not every day that a question this complex can be boiled down to one, single, simple question, but in this one case, I think that perhaps it can and that perhaps this may be managed with sufficient fidelity to provide a one-query heuristic. And so, in the fine and longstanding bad cattitude tradition of “cats out on limbs,” here we go:

“Are you capable of remaining friends with someone with whom you have a significant (or any) political or social disagreement?”

That’s it. That’s the whole analysis. If the answer is “yes,” you’re probably OK. You can be a part of a polity of reasonable people, people who have ideas as opposed to “people who are their ideas.”

Reacting to a difference in views with dismissal, rage, shunning, and projection is a strong marker that your own views are dogmatic and overwrought. It’s the behavior and the inculcation of a cult, a defensive response to avoid inquiry into the indefensible, a rage response to being curled up around a lie that one has made into “my truth.” When ideology becomes identity, all ideological disputation feels like an attack and even erasure. And humans respond with their most profound self-defense mechanisms under such conditions.

This can literally function as a diagnostic tool. If you cannot have a discussion about it without exploding into rage and ending friendships and family bonds, that’s the “check engine” light on your personality and psyche. And probably, all is not well.

This becomes especially acute in a place like the US, where you’ve seen an unusual sort of rarification and radicalization. The simple fact is that the center of US politics has drifted quite a lot to the left since the 1980s and 90s, profoundly so. The positions of typical people on ideas like gay marriage, drugs, sex, explicit lyrics, nudity in movies, welfare systems, and 100 other things have all moved sufficiently far to the left that being a Trumpist Republican today mostly means you would have been a Clintonite in the 90s and a “deep” Democrat radical back in the days of Reagan.

What today gets called “hard right” by the left was “center leftism” in times that an awful lot of people seem to pine for as “better.” What currently occupies the role of the “progressive left” is a set of policies and preferences for which there was basically no American analogue 30 or 40 years ago, a wide swing of the pendulum well off the edge of the map, the kind of swing that brings down serious reflexivity.

And again, “can you have a civil conversation with someone who disagrees with you?” starts to become a profound tool for both self-analysis and the analysis of others, a mental state and societal barometer that tells you when storms are coming (or perhaps that they are already here).

A reader challenged me the other day to consider “where the truth might lie in the center,” and which of these issues also apply to the right, and how they were finding expression. It was a good and honest discussion, and a good question. I asked him, “So what would you cite as an example?” and he cited those on the right who are so convinced that 2020 was a stolen election as to be impervious to evidence.

I do not find this choice particularly convincing, as this seems like a situation with a highly questionable fact pattern and data and inquiry lacking in a fashion as to be prejudicial toward “cover-up,” and that when posing my question above, I find that most on the right are capable of still being friends with people who say, “The election was the election, accept it,” or “I’m not sure anything out of the ordinary happened.” Families are not splitting over the 2020 vote because folks on the right cannot bear to hear someone say, “Biden won.”

But it did set me to thinking, and ranging back through history and looking for a right-wing analogue to the frothing, unreasoning behavior we see from much of the edgelord left factions at present, the one that really popped for me was the anti-abortion movement of the ’80s and ’90s. There was real violence there. Bombings, attacks, spitting, frothing hate, and friends and family disavowed. You had protesters standing outside of clinics screaming in the faces of women, spitting, pushing, creating bad situations that were in many cases, reminiscent of what we see now with the anti-ICE gang and saw in 2020 around BLM. Had social media been a thing then, I suspect it would have been magnitudes worse, acting as both accelerant and spread vector.

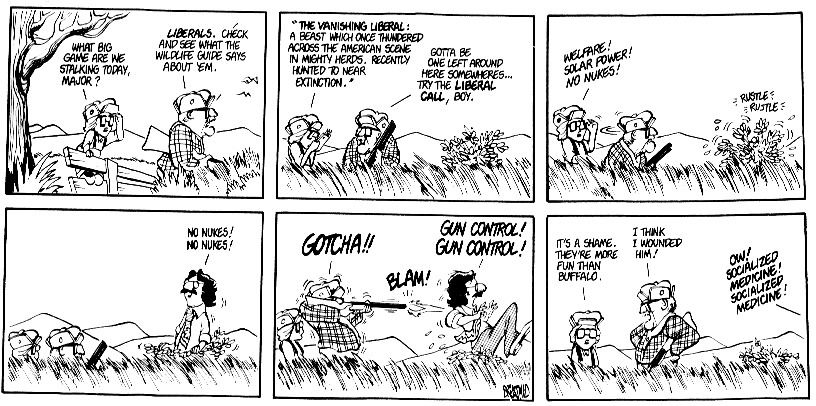

A Classic Bloom County cartoon about Liberals (a little humor can be a good thing): r/Liberal

It’s worth remembering that at that time, the right had been so ascendant for so long in the US that people made jokes about liberals going extinct. But, in the classic proaxis of Greek tragedy and Hegelian dialectic alike, the extreme wing of a party gains overmuch control and drags the group’s platform into precincts it ought not occupy and thereby creates a tipping point by which another choice looks increasingly preferable:

Groups overly accustomed to being in the majority and wielding power free from critique tend to become blasé and entitled about their position. They speak to fewer and fewer who disagree and are more effective and diligent at silencing dissent.

And this undoes them.

Hubris calls down nemesis, and nemesis lays pride low.

There was a large-scale changing of minds and a shift from the “religious right” of Oral Roberts and the “Moral Majority” of Jerry Falwell et al., and back more toward something that found consonance with the American mind and sensibilities. The 90s were a blend of Clinton (who tried to take us far too far left in his first two years) and Gingrich and the “Contract with America” that actually balanced the fricking budget without doing anything crazy. The 90s were a great time in America, prosperous, largely peaceful at home, culturally fun, expansive, and tolerant. It seemed like a sweet spot. But pendulums keep swinging.

I suspect that the collapse of the Soviet Union is a deeply underrated driver for American society, particularly academia. The Cold War was a pervasive societal anchor, a unifying external enemy, and a clear “us/them” binary where “America is for freedom and free markets” and “the other guys are Marxist/collectivist tyrants who need walls to keep their people in.” And, alas, in no small irony, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down that wall” also tore that unifying pole star from the American sky. (Chesterton must be laughing himself to pieces.) The fall of communism begat the rise of political correctness, which underwent metastasis into “woke” and begat all the ideology of offense and aggrievement, children of Marxist and post-modern matings.

The policing of institutions against such ideas fell away. The war was won, why worry? An immune system turned off and went to sleep, and our universities and increasingly the whole of the US public school system were colonized by a Marxist ideology we had stopped seeing as a problem.

The problem with aggrievement theory and intersectional identity war is not just that it is inherently coercive and divisive; it’s also that it’s inherently subtractive. If I may only gain status by being “more oppressed than thou,” then those seeking to stay atop the greased pole of power are set in constant conflict. This is seemingly how all Marxist structures wind up tearing themselves to pieces in purges and ideological purity tests, and the reason I think that we’re seeing so much of this on the left right now, as opposed to the right, is not an inherent feature of left or right. Both are fully capable of oppression, self-delusion, idiocy, and atrocity. It’s a function of the fact that the left has been, for so long, so ascendant. They have been the ones in power and, like the right in the late 80s, have become the ones who have overreached and become overly ideological in a fashion out of step with most of us, our society, and our social contract.

It’s worth discussing the fact that the question above, “Are you capable of remaining friends with someone with whom you have a significant political disagreement?” is always and must be subject to certain boundary conditions and limitations. It cannot be absolute.

If someone’s political belief is, “I support child slavery and men marrying 12-year-old girls against their will and a right of husband rape accruing thereto, with allowable vigilante justice imposed on any who sin or speak against this” (quite literally going on in Afghanistan right now and quite in keeping with the tenets of Sharia law), then yeah, you know what, we can’t be friends, and I’ll war to stop you from acting in such a fashion or trying to impose it upon me and mine. This is far too far from a Western idea of social comity and social contract.

When you hit a set of impositions like this, it’s a sort of civilizational strike point. It causes a rapid and implacable rebound as the civilizational substrate recoils away from something it perceives as evil or anathema. People react viscerally and see those espousing views that have gone too far as “other” and as “enemy,” and the imposition of such upon others against their will as a form of conquest.

The right went too far in the 80s, and terms like “the Moral Majority” became an impositional aristocracy run by some debased people who would no sooner get done denouncing homosexuality to drive donations from the TV audience than get caught having drug-fueled sex with a rent boy in a seedy motel, a pattern that finds an unpleasant mirror today in the number of gender activists who keep getting caught in child rape and porn.

Just as the bumper of “making kids who do not want to pray in schools” and “screaming at and assaulting young women who do not share your view about life beginning at conception and blowing up abortion clinics” jarred America sharply to the left, today the “pray the gay away” has been replaced with “hormone injections and physical mutilation to change the gender of the prepubescent,” ideologies of hatred and self-hatred for “whiteness,” and an oddly uncritical invitation to Islamists whose self-described goal is global caliphate and Sharia. And just as society rebounded left in the 90s, it now rebounds right in the 2020s.

There were bridges too far into ideology, and it’s interesting how public schools are always such a concentration and flashpoint. In the 90s, it was, “Teachers should not force children to pray or vilify homosexuality.” Today it’s, “Teachers should not be stirring up racial animosity and self-hatred or leaning on confused kids with sexual and gender topics way past their capacity to deal with and pushing gender change that ‘parents don’t need to know about.’”

Indoctrinating the kids into anything always seems like the bumper, and I suspect that it’s both a safety valve and a canary in a coal mine.

The simple fact is this: the core American value is that things like religion and sexuality belong in the home and not in the school.

This is the province of the family, not the state. The canary gets ill when schools abandon this. It seems like a marker that one faction or the other has grown overbold in its power. They simply find the public schools too irresistible a temptation through which to proselytize their views, and they grab for the commanding heights of education as indoctrination. (I find this a strong argument for funding students, not systems, and removing curriculum control from the state. It simply cannot be trusted with this power.)

It’s a mechanism that surges from side to side, and that always goes too far in each direction. Left, right, they take turns being the boot and the buttock, but both are groups of humans, and humans all fall for the same foibles. It’s just who we are.

That said, I think that one can make some claims about some definitive differences between left and right, at least in the modern West, particularly today.