![]()

by James Corbett

“Trust The Science!”

This is the mantra of the technocratic tyrants. The rallying cry of the Orwellian thought police. The injunction of the modern-day censors who would seek to rid the marketplace of ideas of any and all opposition.

If you’re reading these words, you already know this. Or you should know this, given that the reason I was censored from ThemTube back in 2021 was because I dared to produce a podcast about the philosophy of science that sought to interrogate and dismantle the “Trust The Science!” injunction.

Let’s cut to the chase: in this post-COVID era, anyone with their head screwed on straight knows that “Trust The Science!” is a stupid, baseless, self-refuting piece of nonsense that is wielded by authoritarians as a cudgel against political dissent.

But as stupid as the “Trust The Science” phrase is, it’s about to get even stupider.

Why? Because a story emerged last month that completely undermines whatever misplaced faith the average propaganda-swallowing rube still harboured about the trustworthiness of “the” science and the supposedly self-correcting peer review process that “the” science is built on.

Strap in, folks. This story is bonkers. And it points to a future that’s so horrifyingly dystopian that not even the “Trust The Science!” thugs will be able to defend it.

THE OLD PROBLEM

Remember the “Sokal affair”?

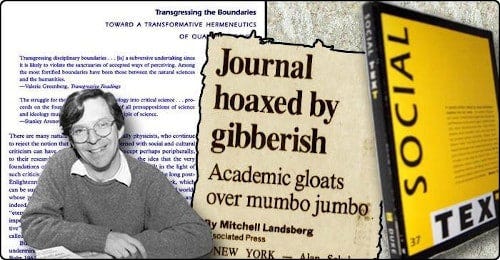

You might not know it by name, but I’ll bet you heard the story. Back in 1996, Alan Sokal was a physics professor at New York University and University College London who was, in his own words, “troubled by an apparent decline in the standards of rigor in certain precincts of the academic humanities.” Rather than write some scholarly treatise about his concerns, however, he decided to demonstrate the problem in a provocative (and hilarious) way: by hoaxing a peer-reviewed humanities journal.

Sokal recounts:

So, to test the prevailing intellectual standards, I decided to try a modest (though admittedly uncontrolled) experiment: Would a leading North American journal of cultural studies—whose editorial collective includes such luminaries as Fredric Jameson and Andrew Ross—publish an article liberally salted with nonsense if (a) it sounded good and (b) it flattered the editors’ ideological preconceptions?

Unsurprisingly, the answer to that question was an emphatic “Yes!”

Specifically, Sokal wrote “Transgressing the Boundaries: Toward a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity,” a perfectly incomprehensible piece of balderdash that seeks to deconstruct “the long post-Enlightenment hegemony over the Western intellectual outlook” by critiquing the very language of science—mathematics and logic—and its “contamination” by “capitalist, patriarchal and militaristic” forces.

“Thus, a liberatory science cannot be complete without a profound revision of the canon of mathematics,” Sokal’s satirical paper concludes before conceding: “As yet no such emancipatory mathematics exists, and we can only speculate upon its eventual content.”

Along the way, he engages in an impressive-sounding but completely irrelevant discussion of esoteric concepts from theoretical physics, including “the invariance of the Einstein field equation under nonlinear space-time diffeomorphisms” and “whether string theory, the space-time weave or morphogenetic fields” will ultimately provide the answer to the “central unsolved problem of theoretical physics.”

In his post-hoax confession, “A Physicist Experiments With Cultural Studies,” Sokal notes that he deliberately peppered the article with silly pseudoscientific gibberish “so that any competent physicist or mathematician (or undergraduate physics or math major) would realize that it is a spoof.”

So, why did the article pass the muster of peer review? In Sokal’s estimation:

It’s understandable that the editors of Social Text were unable to evaluate critically the technical aspects of my article (which is exactly why they should have consulted a scientist). What’s more surprising is how readily they accepted my implication that the search for truth in science must be subordinated to a political agenda, and how oblivious they were to the article’s overall illogic.

Stroking the egos of the editors of Social Text by suggesting that physics was too important to be left up to actual scientists and instead needs to be supplemented with critical theory reflecting feminist and anti-capitalist ideologies, the nonsense paper was, naturally enough, accepted for publication and duly printed in Social Text‘s Spring/Summer 1996 issue on “Science Wars.”

Sadly, this hoax did not sufficiently shame the editors and peer reviewers of the humanities journals into doing a better job. On the contrary. It led, over the ensuing decades, to a number of similar (and increasingly ridiculous) hoax papers being published.

Remember the “Grievance studies affair”? In that Sokal-like hoax, which took place over 2017 and 2018, three separate authors—Peter Boghossian, James A. Lindsay, and Helen Pluckrose—wrote not one but twenty separate hoax articles to demonstrate that nothing had improved since the time of Sokal’s original gambit. If anything, the development of critical social theory and so-called “grievance studies” had actually made things worse in the intervening two decades.

In order to really push the experiment to its limits, the trio ensured that “each paper began with something absurd or deeply unethical (or both) that we wanted to forward or conclude.”

Some examples of papers that were not merely submitted during this raid on academia included:

- “Human reactions to rape culture and queer performativity at urban dog parks in Portland, Oregon,” a paper published in Gender, Place and Culture that purported to address “questions in human geography and

the geographies of sexuality” by observing the behaviour of dogs and dog owners at dog parks to “determine when an incidence of dog humping qualifies as rape”; - “When The Joke Is On You: A Feminist Perspective On How Positionality Influences Satire,” a paper accepted for publication by Hypatia, a leading feminist philosophy journal, which argues that academic hoax papers are in fact a “sophisticated but empty form of privilege-preserving epistemic pushback that seeks to resolve epistemic discomfort by mimicking certain ideas convincingly so as to offer them up for ridicule to

others who are similarly epistemically protectionist”; - “Our Struggle Is My Struggle: Solidarity Feminism As An Intersectional Reply To Neoliberal and Choice Feminism,” a paper accepted for publication by Affilia: Feminist Inquiry and Social Work that—the hoaxsters later admitted—was “based upon a rewriting of roughly 3,600 words of Chapter 12 of Volume 1 of ‘Mein Kampf,” and involved swapping out Hitler’s anti-Jew invective for the anti-patriarchal invective of modern femi-Nazi-ism; and

- “The conceptual penis as a social construct,” published in Cogent Social Sciences, which argues . . . well, I’ll let you read that one for yourself.

Of course, all of these papers were either retracted or rejected for publication . . . once the hoaxers admitted the hoax to The Wall Street Journal. It was only after the trio came clean that the “respected” and “peer-reviewed” journals—gatekeepers of “the” science—realized they’d been had, setting off a firestorm of publicity and public hand-wringing about the state of the social sciences.

“But ACKSHUALLY,” inject the defenders of The Science, “the journals all retracted and disowned the papers once they were discovered to be fraudulent, which just shows that science is self-correcting after all, doesn’t it? And anyway, the hoaxers are just revealing their insecurities about their own genitalia! Trust The Science, guys!”

. . . But then, why do absurd papers like “Glaciers, gender, and science: A feminist glaciology framework for global environmental change research“—an article published in Progress in Human Geography that calls for the construction of “a feminist glaciology”—continue to get published? (For what it’s worth, that paper was apparently not a hoax . . . but you could’ve fooled me!)

What these hoaxes have demonstrated in dramatic fashion is a point that has been well-known to the academics working in the heart of the academic sausage-making factory for some time: peer review is—despite the assurances of the “Trust The Science!” crowd—no guarantee of scientific merit.

Yes, normal human beings who make their living in the free market by providing products or services of use to their fellow community members have known for a long time that all is not well in the land of “the” science, where increasingly bought-and-paid-for researchers make their living by scrabbling for government handouts or selling themselves to the highest corporate bidder.

But—and I get you’re going to have a hard time believing this—as bad as all that is, it pales in comparison to the new problem that cropped up last month.

THE NEW PROBLEM

Surely human-generated hoax papers being published by “respectable” academic journals are the bottom of the barrel when it comes to “the” science, isn’t it?

Nope.

Back in 2005, a team of MIT grads created “SCIgen – An Automatic CS Paper Generator,” a program that “generates random Computer Science research papers, including graphs, figures, and citations.”

Slate did an exposé on the MIT project in 2014, in which it summarized: “Thanks to SCIgen, for the last several years, computer-written gobbledygook has been routinely published in scientific journals and conference proceedings.”

What should be doubly shocking to those who have hitherto unquestioningly trusted “the” science is that between 2005 and Slate’s 2014 exposé, unscrupulous SCIgen users had already managed to get 120 of their algorithmically-generated gibberish articles published in academic journals.

This remarkable feat of deception generated much hand-wringing from the scientific community and caused science communicators to spill gallons of (digital) ink writing soul-searching articles about where the hallowed institution of peer review went wrong and how academics can work together to right the ship and restore public faith in the institution of Science.

So, did all this sanctimonious soul-searching result in the end of the era of gibberish articles?

Nope.

In fact, a 2021 study found that a whopping 243 SCIgen-generated papers had been published by academic journals. Of them, only 12 had been retracted and another 34 had been silently removed. In other words, even years after the problem was first exposed, there were still hundreds of unretracted gibberish articles cluttering up the scientific record.

But if a nearly-two-decades-old computer program for generating scientific-sounding nonsense sounds a bit quaint in the face of today’s ChatGPT-dominated age of Large Language Models, well . . . you’re right! It is.

Forget the 243 SCIgen-generated fake papers. Last month, The Wall Street Journal reported that Wiley, a 217-year-old stalwart of the scientific publishing industry, was retracting more than 11,300 fraudulent articles and closing 19 journals.

According to the report: